Availability Report Tool

⌛ ~4 min read

Project Info

Role: Product Designer

Timeline: 5 months

Launched: December 2023

Team Structure: 1 Business Analyst, 2 Designers, 3 QAs, and 6 Developers

Impact

Delivered 50,000+ contracted location updates since launch

Monthly capacity data is integrated into the Provider Directory and data dashboard, providing transparency across seven critical mental health levels of care

*Note: Some details have been modified to protect proprietary information.

The Challenge

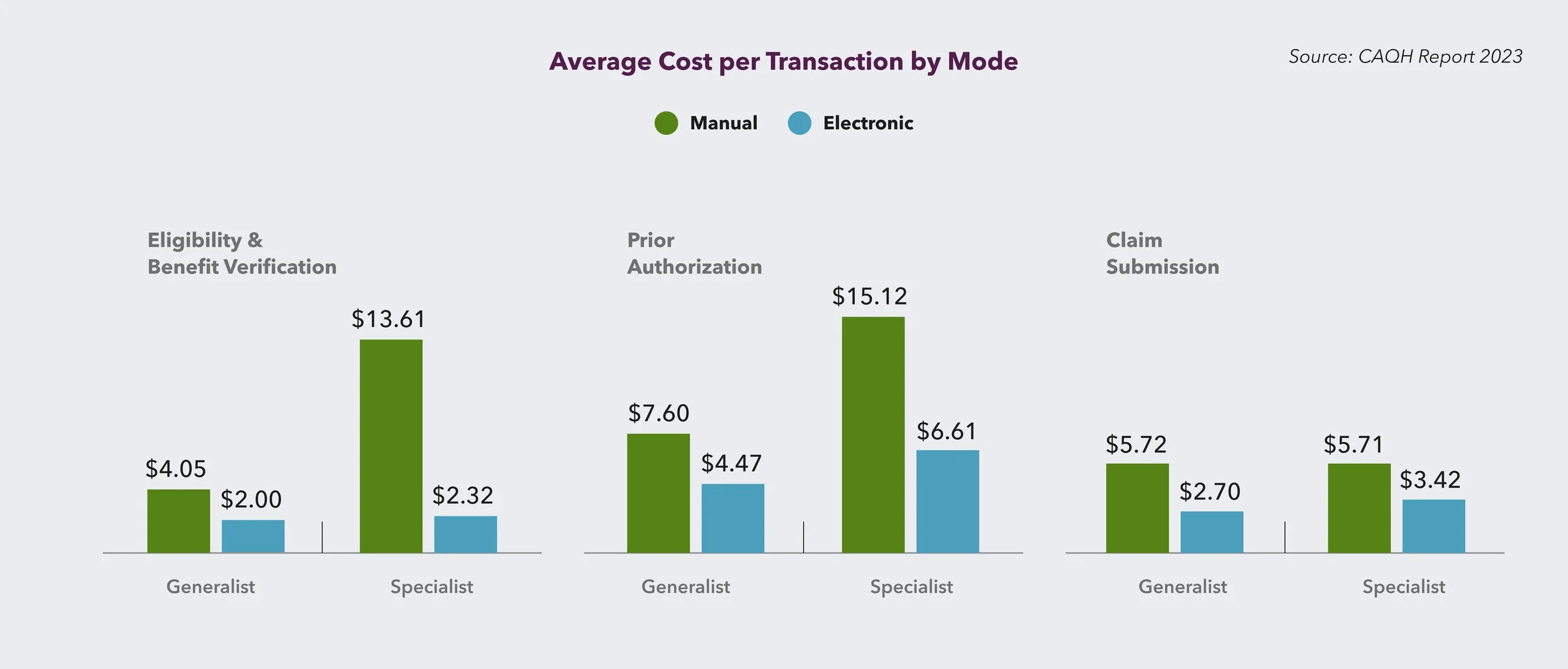

The Steep Administrative Cost

According to The Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare (CAQH)'s 2023 report, behavioral health providers spend an average of 24 minutes (or $14) every time they check a patient's insurance coverage. That's three times longer than generalists due to more complex requirements and services.

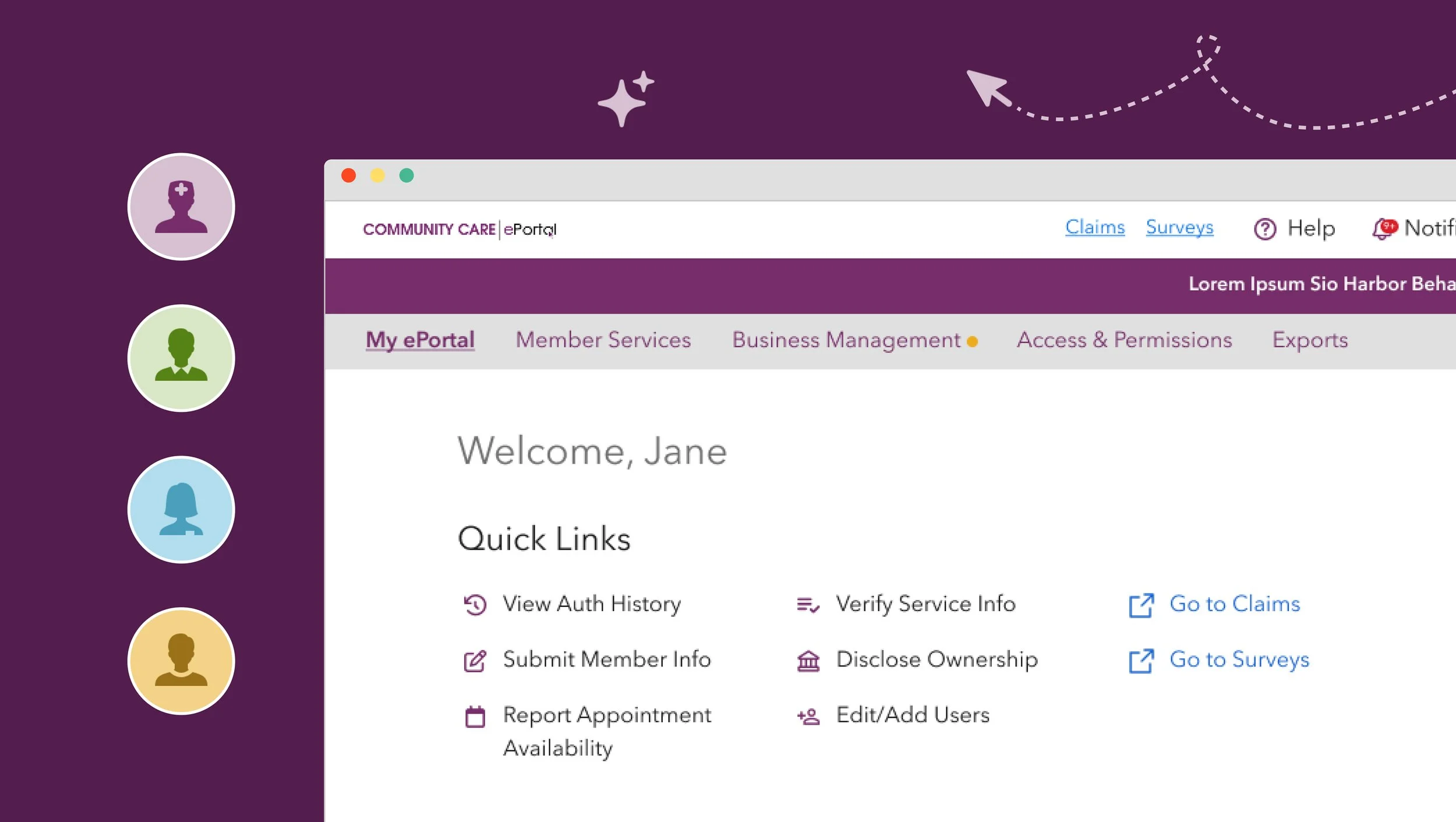

So when our team was tasked with yet another online report—this time to track providers' appointment availability monthly—we faced a classic UX dilemma. Yes, the data would help members find care. But we were asking already-overwhelmed providers to do one more thing.

*Availability report final design

My Process

As an experienced designer, I knew the solution wasn't just about the interface—it was about understanding the ecosystem and the friction points. Who touches this data? When? Why?

I started with stakeholder interviews to understand the current state. Through conversations with five care managers (two who'd previously worked provider-side), a different picture emerged.

"There are so many waitlists now that no one is desperate for cases," one care manager told me. "They can't staff the ones they have."

The real motivation to update availability? Stopping the interruption calls about non-existent openings.

The Availability Nuance

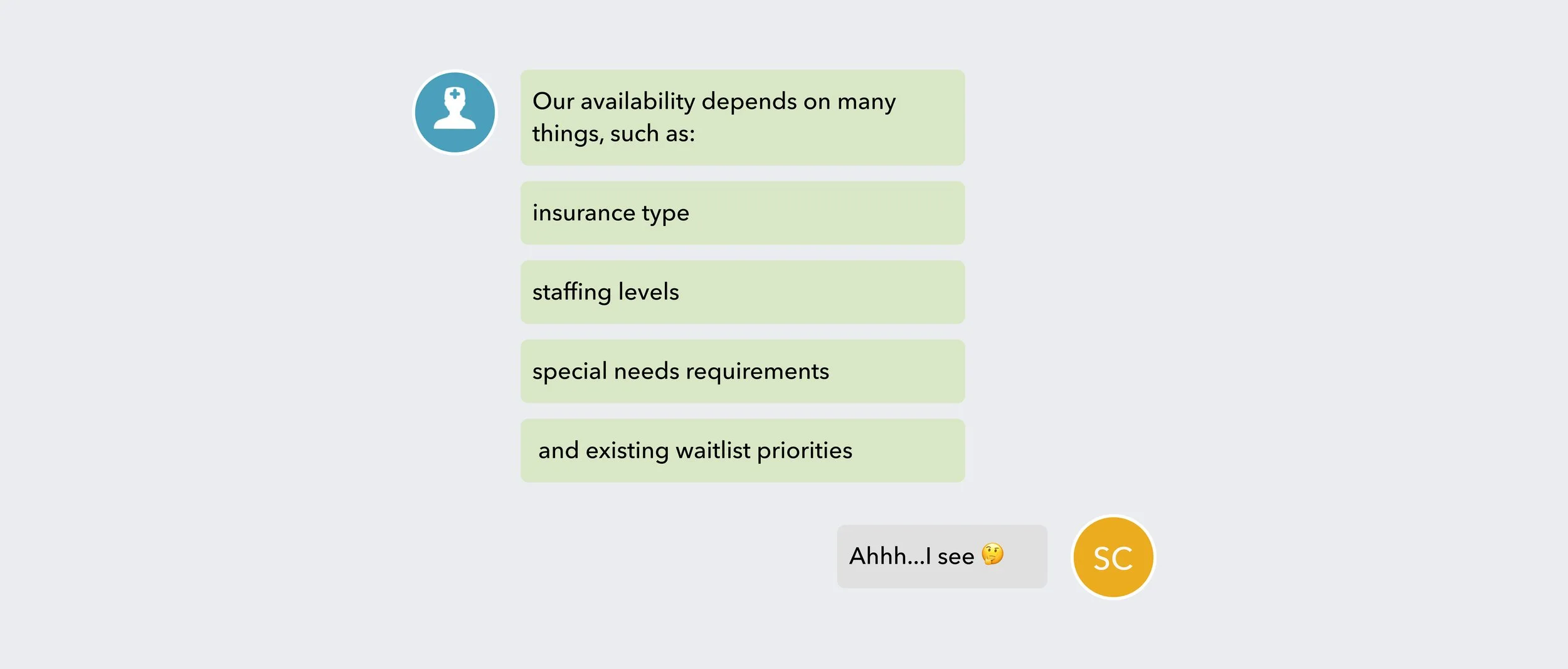

“Are you accepting new patients?" sounds like a simple yes/no question.

It's not.

Secondary research revealed that accepting new patients and having appointment availability are two different things. A provider might say "yes" to new patients but have a three-month wait. Our stakeholder interviews uncovered the factors that influenced their availability.

No wonder providers hesitated with a simple binary answer. They didn't want to say "yes" and be held accountable when reality was more like "yes, but..."

What Actually Works (And Our Constraints)

Care managers built their own system over time: emailed reports, in-person meetings, and update frequencies that matched each service's volatility. Some services needed daily updates; others barely changed week to week.

But we needed to translate that flexibility into an online tool that providers would use. Direct conversations got honest updates; forms got ignored. Our challenge was building something in between.

Design Decisions

Embracing Imperfect Data

With emailed capacity reports already in place, another nuanced multi-field online form would likely see low compliance. So, we set success metrics early: adoption rate over data granularity. This helped us make tough trade-offs with confidence.

Our first instinct was to import the care managers' existing reports—they captured all the nuanced data we needed. But those open-ended reports wouldn't integrate with our directory infrastructure and required constant cleanup.

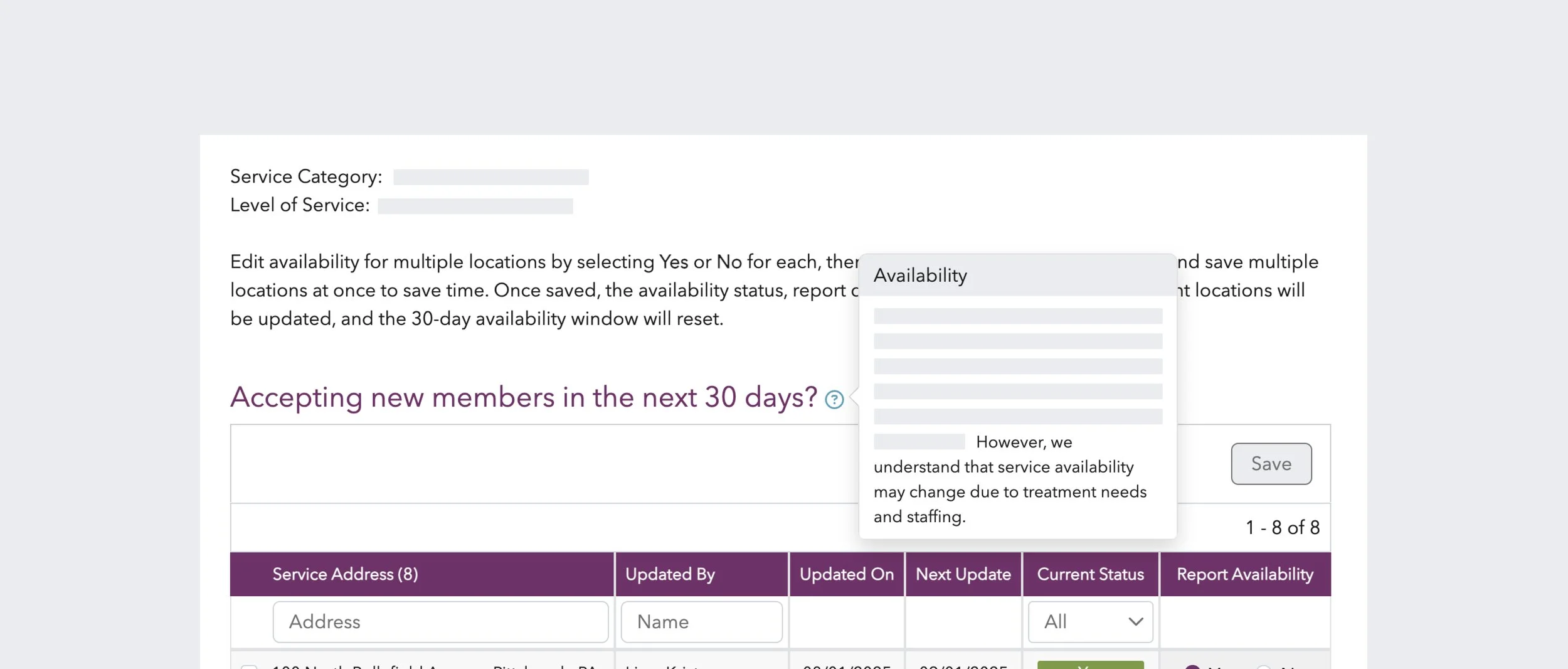

So the product manager and I went back to the drawing board. Instead of fighting for perfect data, we'd use Yes/No as our minimum viable data point. To address providers’ concerns, I added contextual help text that reassures them they won’t be held accountable for nuanced or partial availability.

It wasn't ideal, but 80% compliance with basic data across numerous locations beats 20% compliance with perfect data from a handful. Every design decision is mapped to business value: compliance (avoiding penalties), efficiency (reducing member calls), and member satisfaction (finding care faster).

The Two-Filter Solution

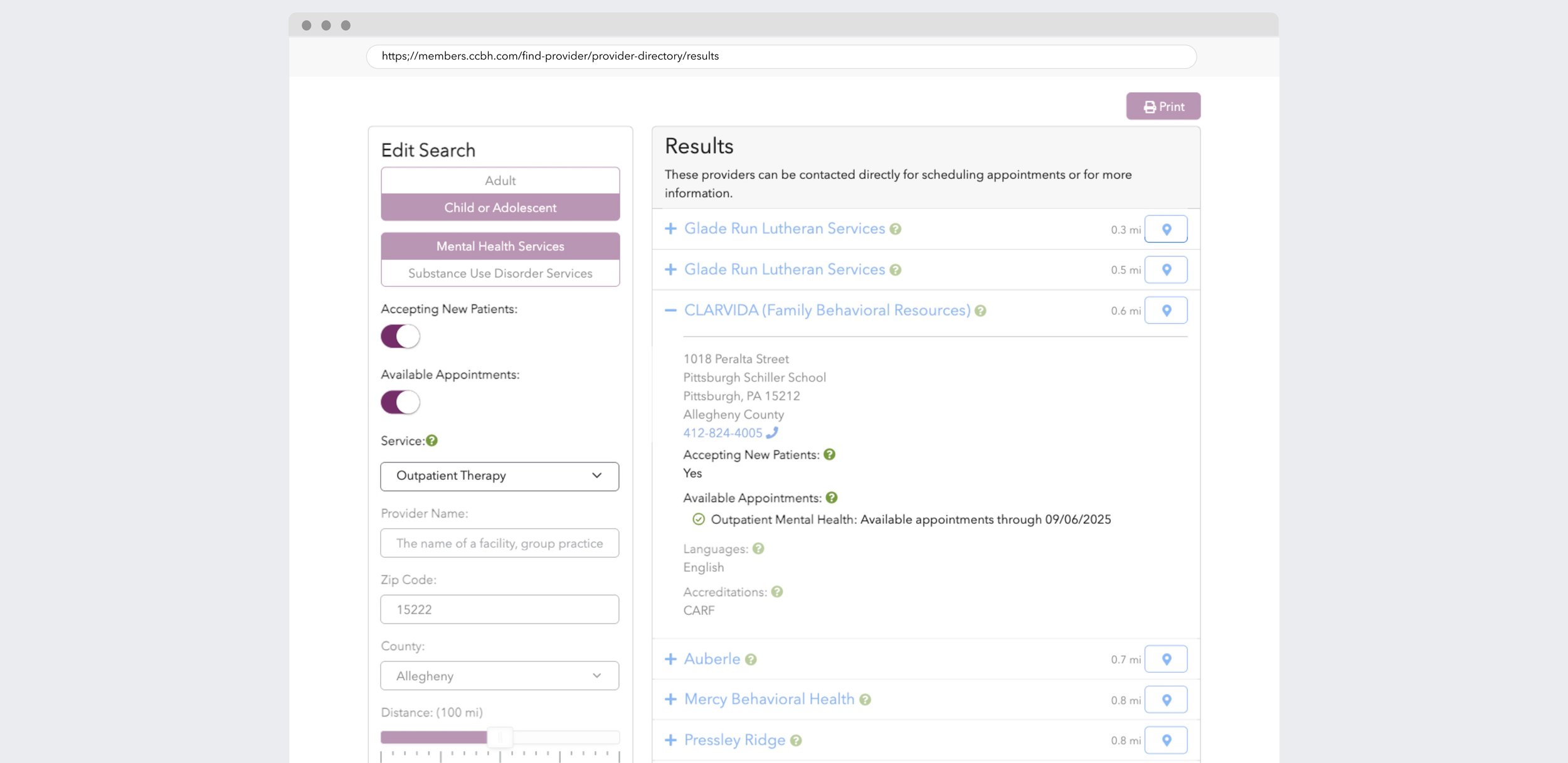

Research showed that accepting new patients ≠ having appointments available. With regulatory requirements to meet, we got creative.

Instead of starting with data, we focus on friction points. Members search with different needs: some are in crisis, others are planning ahead. Our priority was to support both mental models in the provider directory.

Phase 1 casts the widest net—surface any provider with capacity anywhere. Help urgent members start their search. Phase 2 added precision—show exactly which locations offer which services, with timestamps for reassurance.

The result was two search modes: "I need help now" and "I need the right help in the right place."

Same data, viewed through two lenses, each serving a real need.

Designing for Delegation

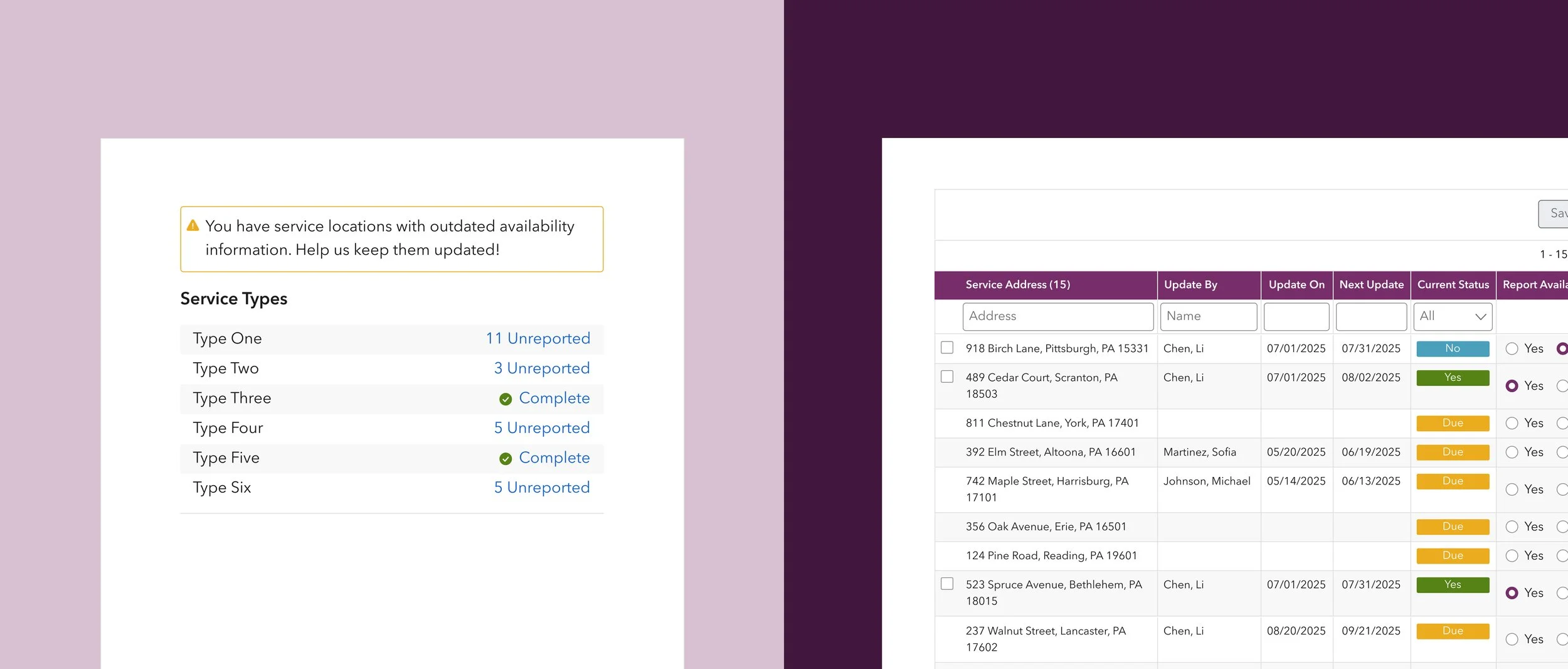

We learned that people who knew the availability (directors) weren't the ones entering the data (admin staff). Rather than fighting this workflow, I decided to design for it.

Workload visibility - We showed unreported location counts upfront so admin staff could gauge the effort before starting, instead of abandoning the task halfway.

Efficient navigation - Admin staff can quickly find assigned locations among dozens of entries. Names and timestamps created accountability trails when multiple people shared the work.

Preventing Biased Data

During usability testing, I observed a behavior that could compromise data quality: users were checking off locations and batch-submitting the same answers as last month without verifying the data.

To address this, we introduced conditional logic. Locations with up-to-date information retained their checkboxes for quick, timely updates. Locations that were overdue, however, reset with no checkboxes and previous answers, requiring users to make fresh decisions. This intentional friction slowed the process just enough to encourage data accuracy.

While auto-save could have streamlined the experience, performance constraints led us to opt for batch-saving instead.

What I Learned

Compliance Deadlines Trump Design Ideals. In healthcare UX, compliance comes first. Missing federal requirements means penalties that could impact member access to care. This meant shipping two filters based on the same dataset rather than building a tailored solution for appointment availability.

The skill is knowing when to push back versus when to ship and iterate. I've learned to evaluate each decision through two questions: "Could this harm patients or providers?" warrants fighting for change. "Is this clunky but compliant?" means we ship and improve later.

As designer Mehekk Bassi observes, "Good design is only as good as the system that allows it to be executed and defended." In healthcare, that system includes federal regulations, and most of the time our job is designing within those limitations rather than against them.

Design for the Real Workflow, Not the Ideal One. Coming from commercial UX, it's tempting to optimize for "efficiency." But healthcare hierarchies exist for good reasons (sometimes).

Directors' time belongs to clinical decisions, not data entry. So we designed for admin staff as our primary users while giving directors oversight of the data they ultimately own. The key is building trust by working with existing roles, not against them.

Progress Over Perfection Pays Off. Before our tool, members had to work through lengthy call lists to find available providers. Now, even with simplified 30-day data, they can see who's accepting patients and which services have openings.

A perfect system that never ships helps no one. I chose to build a foundation with basic data flowing rather than wait for perfect granularity. Now we have real usage patterns to guide iterations, proving that sometimes simple solutions delivered fast beat complex ones delivered never.